Waterbirds’ monitoring in the Venice lagoon and the role of the REST-COAST project restoration efforts

This article has been developed by:

Caterina Dabalà, Francesca Coccon (CORILA), Francesco Scarton, Chiara Miotti (SELC s.n.c)

The Venice Lagoon, located in the Northwest Adriatic Sea, is the largest wetland in the Mediterranean and one of the most important sites for waterbirds in the Mediterranean basin. It is recognized as the Italian largest Important Bird Area (IBA) and stands as the most significant wintering site for birds in the Country. More than 300 species have been observed here so far, while between 400,000 and 500,000 birds regularly spend the winter among about 20 fish farms, the open basin and along the littoral strip (Basso & Bon, 2016-2023).

Similarly, a huge number of species nest among the many habitats of the lagoon, from the sandy beaches to the numerous saltmarshes, both natural and artificial, and fish farms. Very few recent data were published for the birds which cross the lagoon during spring and autumn migration, apart from the results coming from ringing activities made in some fish farms and dealing mostly with Passerines. Estimates of the number of birds overstaying at the Venice lagoon during their migration journeys have never been attempted, but these must likely be in the order of several hundreds of thousands.

Among the nesting birds, the waterbird community is known fairly well; the lagoon open basin hosts every year between 3,000-5,000 pairs of several species, including some of conservation importance, due to their inclusion in the Annex I of the EU 147/09 Bird Directive, in the Italian Red List with the status of “Threatened”, or because they have a scattered or restricted distribution throughout Italy (Scarton, 2017a). Several species are also nesting in the 10,000 ha of fish farms, but in this case only estimates are available, often referring to some sites or groups of sites.

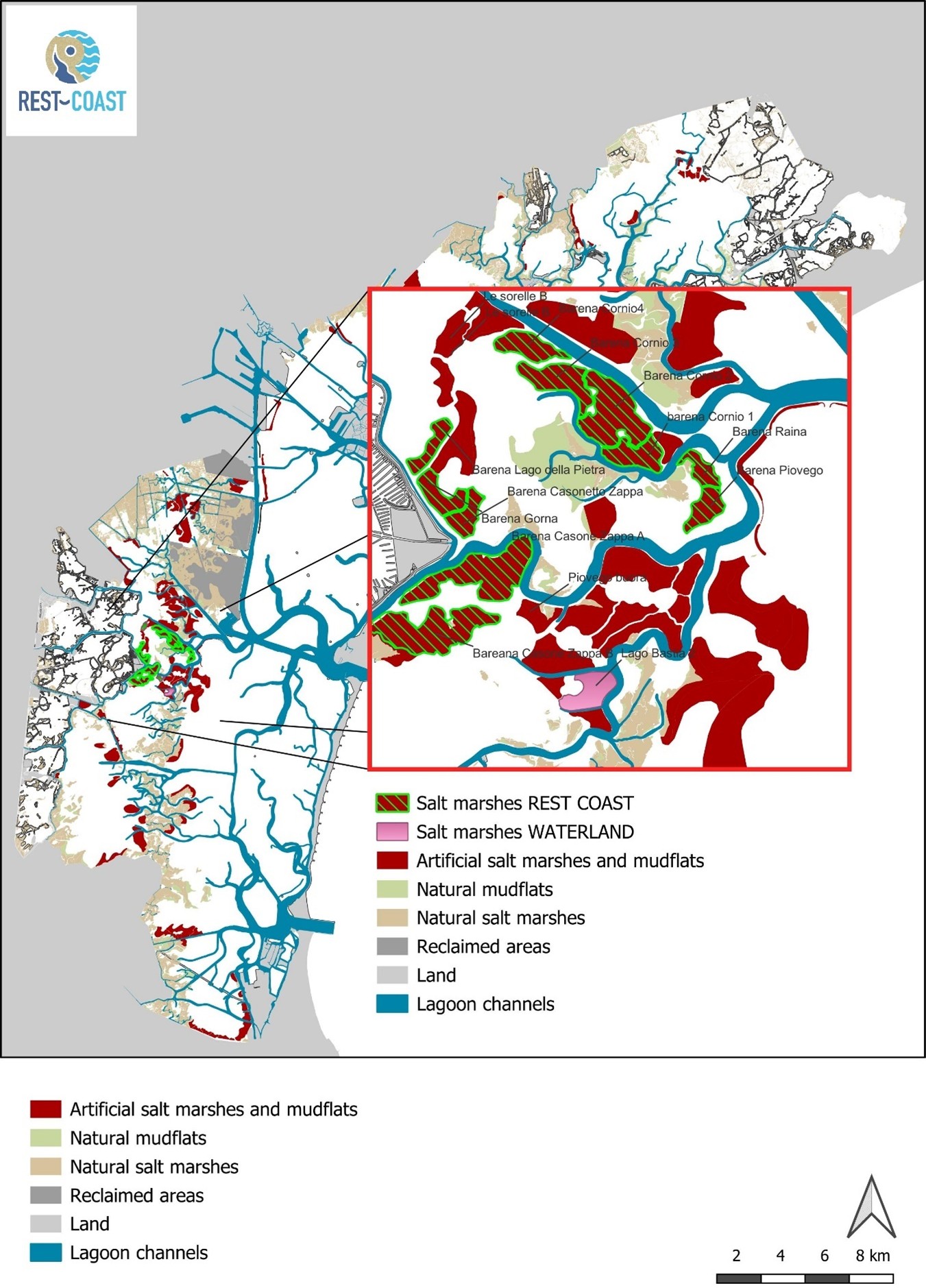

The REST-COAST pilot action to be implemented in the Venice lagoon consists in the restoration of already existing artificial saltmarshes located in the central lagoon (cfr REST-COAST’s Deliverable 6.5). These works aim at reversing the degradation processes occurring in the basin and improving some of the features that hinder the naturalization processes of these artificial structures. By mitigating the saltmarsh border erosion and favouring the conditions suitable for the subsequent colonization of vegetation and wildlife species,

REST-COAST actions will enhance opportunities to expand priority habitat surfaces and boost site-specific biodiversity.

Among the goals of the REST-COAST project is to understand how the NBS, thus the saltmarshes’ restoration in the case of the Venice lagoon, can help in fostering the ecosystem services (ESS) such as water quality purification, reduction of erosion and flood risk, climate mitigation through carbon sequestration and food provisioning, as well as biodiversity. Importantly, through the analysis of past restoration interventions which have been implemented since the ‘90 in the Venice Lagoon, the evaluation of results coming from the on-going monitoring activities (that started in February 2023), and the application of high-resolution spatial models on a lagoon scale, it will be possible to assess the effects of the saltmarshes restoration in terms of ESS improvement, and to identify the up and out scaling restoration strategy.

This paper aims to share the results of the first 3 years (2023-25) of the extensive waterbirds’ monitoring performed in the Venice lagoon, by focusing on quantifying the benefits of the restoration efforts on waterbird populations.

Methods

Surveys aimed at detecting the bird species presence, abundance and distribution were conducted in the whole lagoon by boat, during the high tide periods. The monitoring protocol includes visual censuses and high-definition drone images during each phase of birds’ biological cycle (winter, nesting, spring and autumn migration periods). All the significant roosting and feeding sites and four tidal flats were surveyed. Furthermore, additional surveys have been performed in the breeding period with the aim of detecting the breeding species at their colonies, in the central lagoon. In this regard, each colony was visited at least three times in the period May-July of each year, corresponding to the reproductive season of most of the species, i.e. seabirds (Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern) and waders (Oystercatcher, Redshank, Avocet, etc.).

Figure 1. Lagoon of Venice and REST-COAST pilot site where the restoration interventions occurred.

Results

Results obtained from the first three years of monitoring confirm a regular use of the high-tide roosts and tidal flats in the Lagoon. We found a significant similarity in the abundance patterns along the years, with a peak of individuals in the wintering period, following by a decreasing trend to reach the minimum in the late spring, when the breeding season begins.

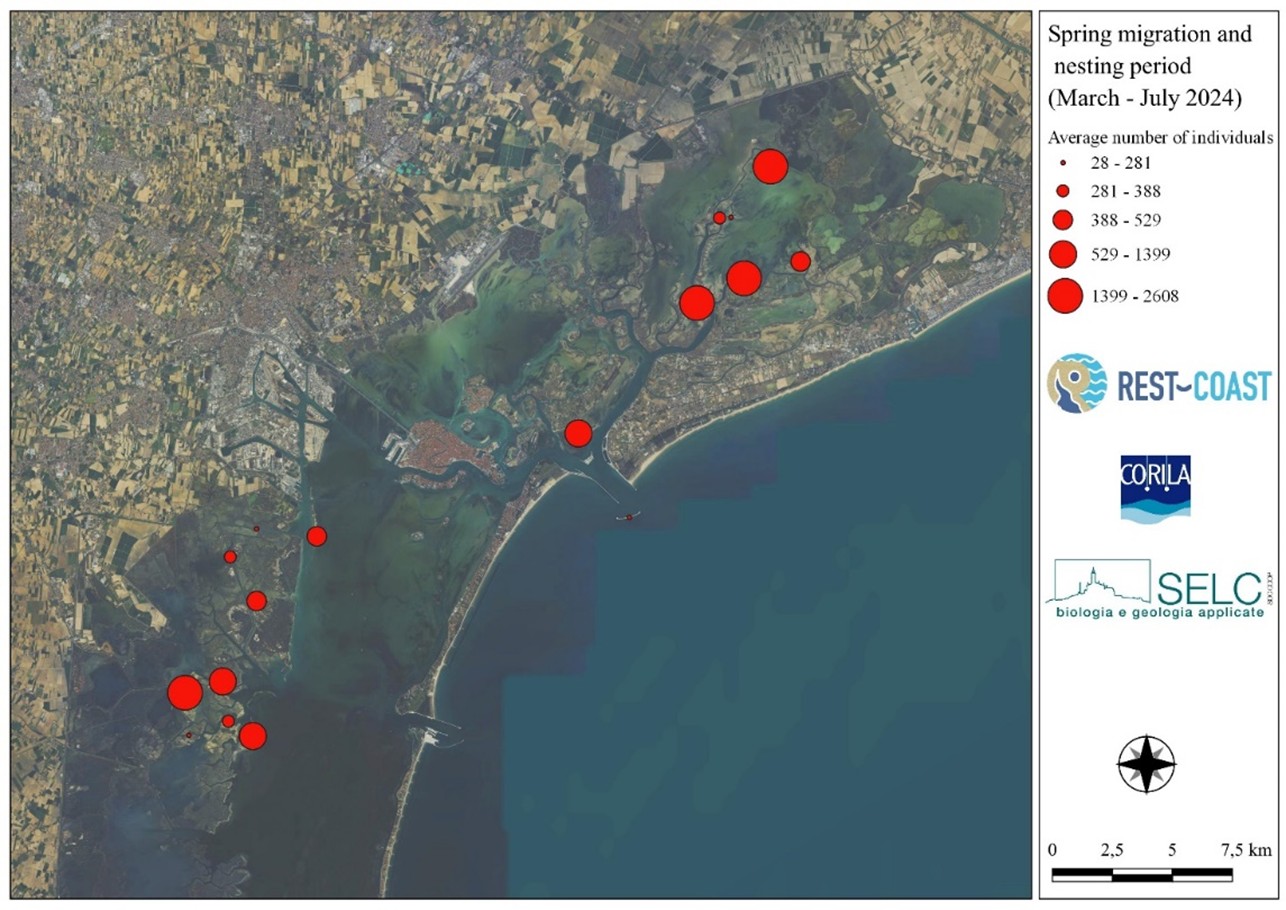

The most important roost in terms of birds’ abundance is the “Barene Dogá” in the northern lagoon (Figure 2). The area is used as a roost by hundreds to thousands of individuals as there is a system of poles and artificial structures called “burghe” (Figure 2, on the top) bordering the edges of the artificial saltmarsh to protect it and emerging from the water even during high tides, offering in this way safe roosting sites to the birds. Furthermore, being in a rather remote area, it is also a little disturbed, and this factor probably positively influences the number of individuals observed.

Figure 2. A visual comparison of birds’ occurrence at the roosts considered in the Rest-Coast project. In the two small pictures: top) Turnstones Arenaria interpres on the top of a “burga”, i.e., an artificial structure filled with stones built to protect the edge of the artificial saltmarshes; and bottom) Curlews in one roost called “Punta La Vecia”, significantly used by thousands of waterbirds also in the past (Coccon & Baldaccini, 2017[2]).

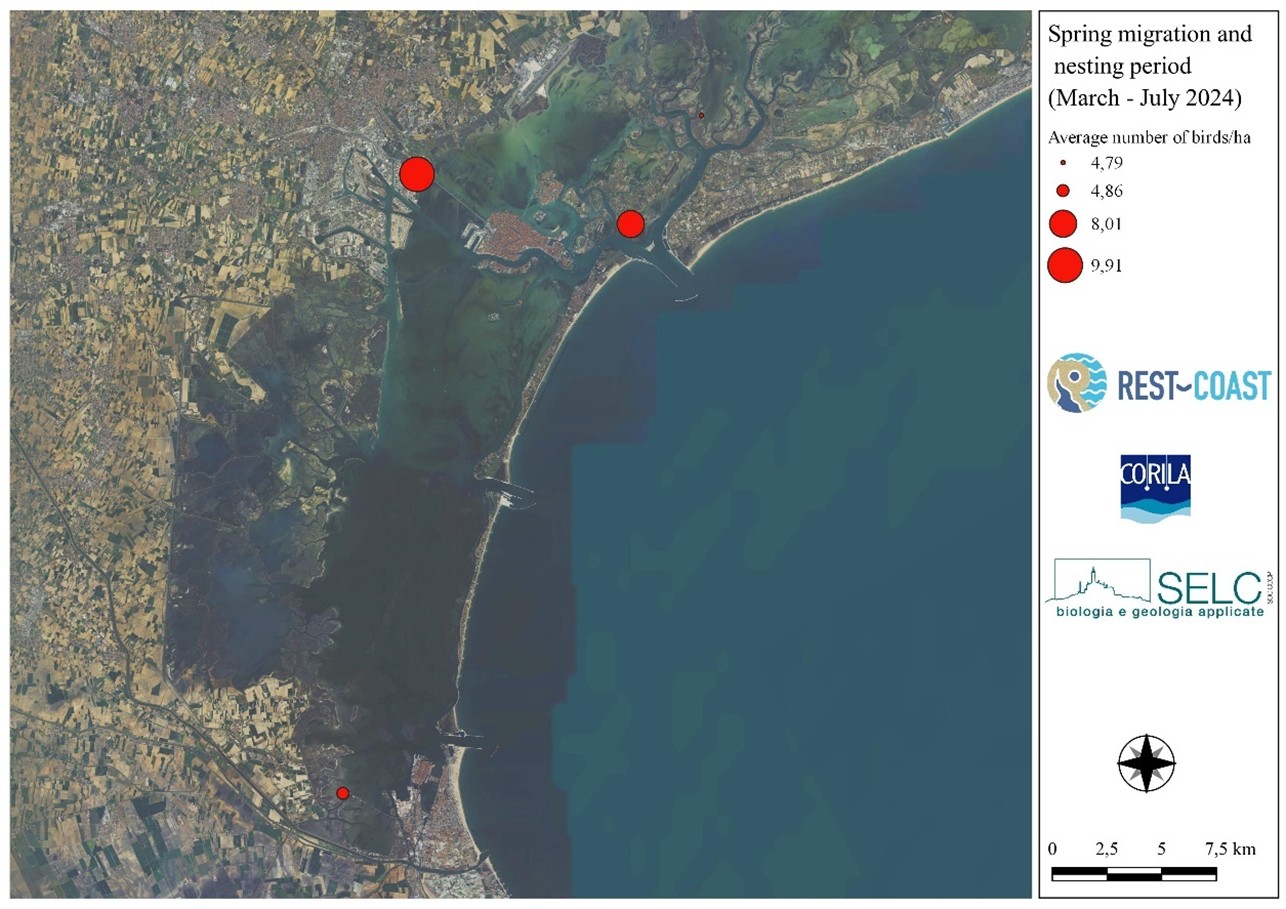

Regarding the tidal flats, the so called “Bacan” and “Marghera” proved to be the most used by birds (Figure 3), especially for feeding, with very similar mean values over the years, in terms of birds/ha. Overall, our results show that the number of waterbirds using these important habitats were stable in the last two years, with a clear preference for the a forementioned sites.

Figure 3. Mean occurrence of birds (individuals/ha) at the four tidal flats considered in the surveys performed within the Rest-Coast project. In the picture, top) Marghera tidal flat; bottom) Oystercatchers roosting at Bacan site.

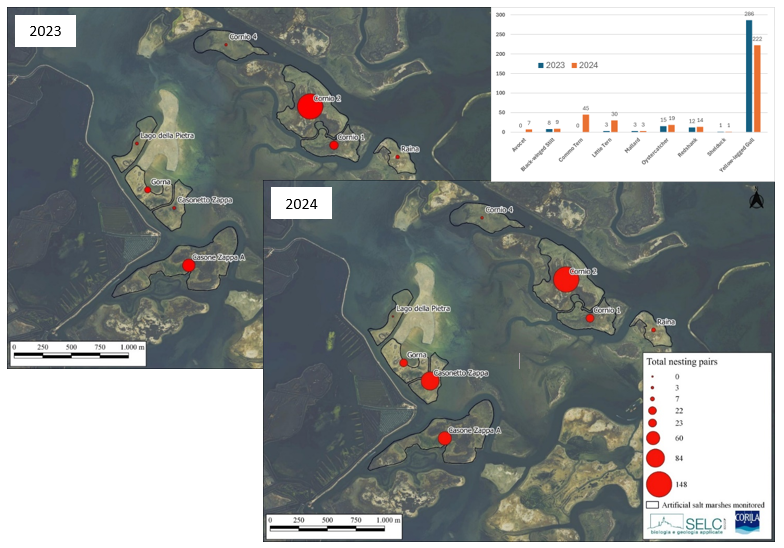

With regard to nesting species, our results (Figure 4) show that, among the investigated artificial saltmarshes, the so called “Cornio 2” and “Casone Zappa A” hosted the largest number of breeding pairs in 2024, mainly belonging to the Yellow-legged Gull, Larus michahellis, representing the 86% of the pairs recorded. This species is known for competing with other more relevant ones (e.g. Common terns) for suitable nesting sites, by colonizing them 1-2 months earlier (Coccon et al. 2018 [1]). These two saltmarshes are both characterized by vast extensions of halophilic vegetation.

The remaining sites had less than 30 pairs, with “Cornio 4”, hosting just two. The second most abundant species was the Oystercatcher, Haematopus ostralegus, with 15 pairs detected, that were found at seven out of eight artificial saltmarshes, thus becoming the most widespread species. The remaining five nesting species occurred with very few pairs, ranging from 12 pairs for Redshank, Tringa totanus, to just one pair of Shelduck, Tadorna tadorna.

The ornithological surveys performed in 2024 revealed a comparable, though slightly higher, number of pairs compared to 2023 (Figure 4). Overall, nine species of waterbirds were registered, most of them nesting in colonies ranging from a few to almost 140 pairs. Although the most abundant species is the Yellow-legged Gull, with a slight reduction compared with the previous year (-23%), the nesting of several species of high conservation importance is noteworthy; among these, the occurrence of Common Tern, Sterna hirundo, which did not nest in 2023, Little Tern, Sternula albifrons, which nested in 2023 with just three pairs, and Oystercatcher is remarkable.

Figure 4. Visual comparison of the number of species nesting at the eight artificial salt marshes in 2023 (above) and 2024 (below). In the diagram: number of breeding pairs recorded in 2023 and 2024, for each species.

With regards to the nearby natural saltmarshes, our results show that just few species are nesting in these sites, with a limited number of pairs. The most abundant species was the Redshank, Tringa totanus, with around 30 pairs, followed by Little Tern having similar numbers. All the remaining species had less than 25 pairs each.

|

|

Figure 4. On the left, a Redshank while brooding the eggs. On the right, some Little Terns in the colony settled on a natural saltmarsh. Frame from the video-camera trapping recorded in June 2023.

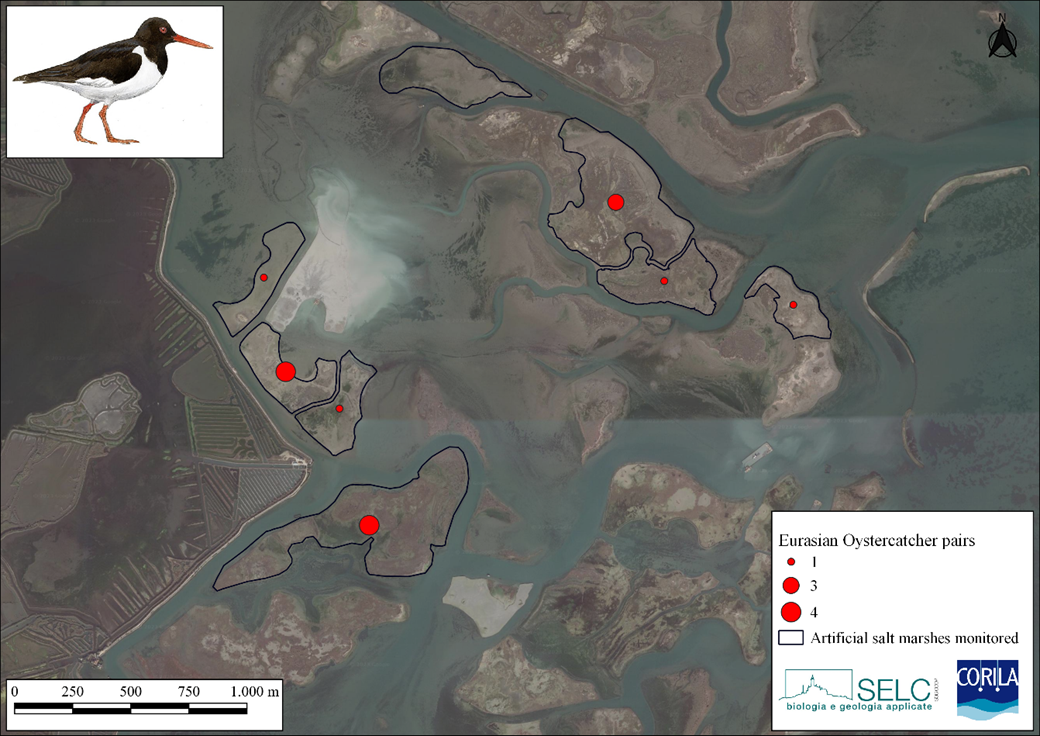

In Figure 5 the map of distribution and relative abundance of Oystercatcher is depicted. The whole population of the Oystercatcher in the Venice lagoon open basin was estimated in around 180 pairs in 2018 (Scarton & Valle, 2021 [4]), while in Italy the value ranges between 300 and 400 pairs (Scarton, 2022 [5]). Therefore, it is of particular importance to highlight that in the study area nests between 5-10% of the whole Italian nesting population of this species.

During the monitoring activities performed in the 2024 reproduction season, 28 pairs of this species were estimated: half of which in the artificial saltmarshes, while the remaining in the natural ones. On the artificial saltmarshes, the Oystercatcher nests are usually found on the top of small mounds, being slightly more elevated than the remaining surfaces. This is a “smart choice” allowing the individuals to avoid the exceptional high tides, such as the one occurred the 14th of June that swept away most of the colonies of the other species.

Figure 5. Number of Oystercatcher pairs nesting at the eight artificial saltmarshes in the central lagoon.

These results highlight the importance of the artificial salt marshes as nesting sites for birds of conservation relevance. Indeed, due to their intrinsic features such as the higher elevation, artificial salt marshes are relatively safe from flooding (Figure 6) while natural salt marshes are often experiencing complete flooding during the nesting season in the recent past. If this trend will continue in the coming years, they may be abandoned by birds in the future. Importantly, it must be added that artificial saltmarshes serve as crucial feeding grounds, offering extensive mudflats that support waders, ducks, flamingos, and ibises, fulfilling an essential role at the lagoon scale.

Figure 6. Nest of Oystercatcher at the so called “Gorna” artificial salt marsh in the Venice lagoon.

Conclusion

The results shown in this article highlight the key role of artificial saltmarshes and tidal flats of the Venice Lagoon as nesting and feeding habitats for waterbirds. Nevertheless, in the two past years (2023 and 2024) we experienced heavy rains and sustained high tide in the period May - early June that caused a heavy loss among the clutches and led to the abandonment of the nesting sites by the individuals.

Despite the emerging challenges of extreme weather events, artificial saltmarshes offer a resilient alternative to natural habitats, supporting bird species of high conservation concern. Tidal flats also provide critical feeding grounds with stable bird densities comparable to other European wetlands.

The REST-COAST restoration actions are crucial to reinforce and improve the ecological value of these valuable and unique habitats ensuring their long-term maintenance and contribution to support biodiversity and lagoon-scale resilience.

[1] Basso M., Bon M. (various years). Censimento degli uccelli acquatici svernanti in provincia di Venezia. Provincia di Venezia - Assessorato alla Caccia, Associazione Faunisti Veneti. Internet: www.faunistiveneti.it

[2] Coccon F., Baldaccini N. E. (2017). Analisi delle variazioni temporali delle comunità ornitiche costiere e lagunari durante i lavori di costruzione del Sistema MOSE. In Campostrini P., Dabalà C., Del Negro P., Tosi L. Il controllo ambientale della costruzione del MOSE: 10 anni di monitoraggi tra mare e laguna di Venezia. 2004 – 2015. Stampa Nuova Jolly, Padova.

[3] Coccon F., S. Borella, N. Simeoni, S. Malavasi (2018). Floating rafts as breeding habitats for the Common tern, Sterna hirundo: colonization patterns, abundance and reproductive success in a Venice Lagoon wetland area over two breeding seasons. Rivista Italiana di Ornitologia - Research in Ornithology, 88 (1): 23-32. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4081/rio.2018.349

[5] Scarton F. (2022). Beccaccia di mare Haematopus ostralegus: In Lardelli R., Bogliani G., Brichetti P., Caprio E., Celada C., Conca G., Fraticelli F., Gustin M., Janni O., Pedrini P., Puglisi L., Rubolini D., Ruggieri L., Spina F., Tinarelli R., Calvi G., Brambilla M. (eds). Atlante degli uccelli nidificanti in Italia. Edizioni Belvedere (Latina): 198-199.